Sunday, 15 April 2012

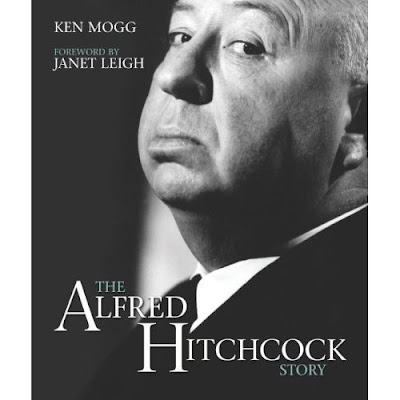

“Willowy, Blonde and Cool": The Icy Blondes, by Philip Kemp in Ken Mogg´s The Hitchcock Story

Posted on 10:22 by Unknown

Hitchcock's ideal woman, at least in his films, was willowy, blonde, and cool. What intrigued him was the hint of

uninhibited passion behind the cool façade; in his own words, "the drawing-room type, the real ladies, who become whores once they're in the bedroom ... Sex should not be advertised.

An English girl, looking like a school teacher, is apt to get into a cab with you and, to your surprise, she'll probably pull a man's pants open."

This revealing quote points to a recurrent (and some would say misogynistic) pattern in Hitchcock's treatment of his heroines.

Time and again in the director's films one of these cool, soignée blonde women is reduced to a disheveled, panic-stricken mess, or reveals unexpected depths of sexual ardor. This could be seen as the psycho sexual equivalent of Hitchcock's love of showing us danger and terror lurking beneath the surface of seemingly everyday events and places,

such as a children's party (Young and Innocent), an art auction (North by Northwest), a quiet London street (The Man Who Knew Too Much), or a sleepy small town (Shadow of a Doubt).

Like Hitchcock himself, the serial killer in The Lodger seems to have it in for blondes: All the women he targets are fair-haired, and we see nervous blondes donning wigs or pulling down hats before braving the foggy streets, while their brunette colleagues laugh smugly.

But the first of Hitchcock's ice maidens to be thoroughly disarrayed was Madeleine Carroll, who spent much of The 39 Steps handcuffed to Robert Donat, so that every time she moved her arm his hand stroked her thigh.

Not only in the film, either. On the first day of rehearsal, when Donat and Carroll had only just met, Hitchcock handcuffed them together and then pretended for several hours to have lost the key.

Hitchcock's mischievous, semi-sadistic treatment of blondes hit its stride in Hollywood, perhaps provoked by the flawless glamour of its screen goddesses.

Joan Fontaine, tormented by the sinister Judith Anderson in Rebecca, fears her husband is poisoning her in Suspicion. Her fears turn out to be illusory (though Hitchcock, if he'd been allowed, would have had it otherwise), but Ingrid Bergman really is being poisoned in Notorious, and again in Under Capricorn.

Bergman was the first of Hitchcock's actresses with whom he became obsessed, maintaining that she returned his passion. He became similarly fixated on Grace Kelly and Tippi Hedren. Kelly was put through it less than her counterparts, though in Dial M for Murder

she was nearly strangled and then tried for murder; but more often she served to illustrate Hitchcock's taxi thesis (as outlined previously), revealing hidden fires behind her reserved, classic beauty. In To Catch a Thief, she makes bold physical advances toward Cary Grant, while in Rear Window

she teases the immobilized James Stewart with a filmy negligee, purring about a "preview of coming attractions." In North by Northwest the alluring but lethal Eva Marie Saint, with her penchant for sex on trains, is equally ambivalent.

This view of the cool blonde as sexually schizoid is made explicit in Vertigo where Kim Novak, having seemingly died as the elegant, fair-haired Madeleine Elster, is resurrected as Judy Barton, a brunette dressed and made up to look as tarty as possible.

But such overt carnality is rejected by James Stewart. Judy must dye her hair, change her clothes, and become Madeleine again before he'll make love to her.

(The analogy with the director, avidly molding his female stars to fit his template, is inescapable.) To Hitchcock, only when a woman's sexuality is concealed is it truly erotic.

In the case of some actresses, it seems that the concealment was too thorough; Hitchcock could do little with the wholesomeness of Doris Day (in the remake of The Man Who Knew Too Much)

or Julie Andrews (in Torn Curtain). Conversely, revealing all too early is dangerous: Janet Leigh, first seen in Psycho half-dressed on a bed with her lover, suffers a terrible fate for her lack of modesty.

The most problematic and extreme instance of Hitchcock's attitude toward his cool blondes was his treatment of Tippi Hedren. "I had always heard that his idea was to take a woman—usually a blonde— and break her apart, to see her shyness and reserve broken down," Hedren later recalled. "I thought this was only in the plots of his films."

But the ordeal Hitchcock put her through in filming The Birds (where she was pecked and gouged by very real, panicky birds tied to her with threads) was matched by his obsessive personal pursuit of her off-screen. Hedren's rejection of his advances strained their relationship during the shooting of Marnie, where her icy blonde image is specifically linked with sexual frigidity.

Hitchcock liked to quote the nineteenth-century French playwright Victorien Sardou's advice, "Torture the women!" — adding provocatively, "The trouble today is we don't torture women enough." Hitchcock, at least, did his best to make up for the omission.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

0 comments:

Post a Comment