Prologue: A Matter of Faith

I would not say that the future is necessarily less predictable than the past. I think the past was not predictable when it started.

Donald Rumsfeld, 2004

On June 6, 2002, Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld boggled the world with assurances that Saddam Hussein had weapons of mass destruction and intended to share them with Al Qaeda. "There are things we know... we know," here marked nonchalantly. "There are known unknowns, things... we now know we don't know. But there are also unknown unknowns... things we don't know we don't know."

The problem for national security was always the unknown unknowns. How can you defend against No Discernible Thing? He struggled to express this pithily. "The absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. It is basically saying the same thing in a different way. Simply because you do not have evidence that something exists does not mean that you have evidence that it doesn't exist." The idea is ticklish, so cryptic and sly it could be a Sufi teaching from Mullah Nasruddin. How do we interpret this banana peel, Rumsfeld's riddle of threat assessment? (1)

It wasn't the first time that a high official proposed that Nothing must be reckoned as the indefinite Something of threat, unless it could be conclusively proven to be nothing at all. During the cold war the United States Air Force, believing forces "under concealment," ICBMs "now operational but undetected," insisted that what could not be seen could be assumed to be invisibly in place.

In 1960 it concluded that the Soviet arsenal was vastly more formidable than anything the CIA's program of aerial reconnaissance had spotted. Strategic Air Command intelligence officers unhesitatingly identified as missiles every smudge and blot on U-2 photographs—a Crimean War memorial, a medieval tower, even the silhouettes of conventional ammunition depots in the Urals. A year later, they tutored the new President's advisers on how, even with the recent introduction of satellite espionage, missile installations might still elude detection.

On the assumption that the Soviets routinely camouflaged their assets, they projected as many as a thousand ICBMs in the Russian inventory, and at least two hundred already squatting on their launchers. Other estimates suggested fifteen. All were wrong. Only four Soviet missiles were operational in 1961. (2)

How could intelligence specialists have been so mistaken? In 1960 Herman Kahn put the problem concisely: "The aggressor has to find one crucial weakness" in his enemy's capabilities, "the defender has to find all of them and in advance." In order to do so, the analyst has to "visualize the possibilities."

Not only was this kind of speculative analysis hard to do, it was hard to persuade anyone to listen. Nearly everybody in the defense community was infuriatingly dismissive. Kahn complained, "Any problem that cannot be proved to exist by objective scientific verification or by legal rules of evidence [was] 'hypothetical.'" In the same June 2002 briefing, sounding very much like Kahn, Secretary Rumsfeld pointed out the merits and snares in the idea of possible threats. "All of us in this business read intelligence information. And we read it daily and we think about it and it becomes in our minds essentially what exists. And that's wrong. It is not what exists." (3)

While this book is not about Rumsfeld and the Bush administration's War on Terror, it is precisely about the unknown unknowns of national security. It is about how analysts in the cold war developed ways to fill in the ciphers of strategic uncertainty. It explores the peculiarly inventive quality of strategy, how uncertainty becomes the wellspring of extravagant threat scenarios. However much nuclear war planning—the fighting, termination, and survival of it—was presented to the public during the cold war as a practical question for scientific deliberation, war planning could never be a matter of fact. Whether or not humankind could survive a nuclear war could only be resolved with reference to one's own beliefs about the social and natural world. To flesh out a world where clever men fashioned Something out of Nothing, in this book I offer a tale about Herman Kahn, a virtuoso of the unknown unknowns.

Once you start trolling for possible threats, you begin to flinch, to anticipate. Your fears find corroborative form in the inscrutable flotsam blown this way and that by the world. When I was writing this book, the natural order of things took on the aura of a surprise attack. During summer nights in Atlanta, I was occasionally startled awake by an intolerably bright flash, followed by the house-shuddering crack of thunder nearby.For a microsecond, southern storms were no longer the welcome pulse of water streaming back to earth, but became the light, shock, and blast of a nuclear explosion. As the boom rumbled through my body, something peculiarly historical happened, the improbable yet actual, the hard-to-grasp, hard-to-think-for-more-than-a-moment possibility of nuclear war had arrived. Now. In our present. Not muffled in kitsch design or bygone styles of feeling, but now.

In 1998, when I first considered how I might begin this book, I thought the American power to wage nuclear war was a fact of contemporary life that somehow had been repressed. Most people seemed to have forgotten about the existence of nuclear weapons in our world. A few years after the collapse of the USSR, a few ICBM silos were renovated into dwellings for families who reveled in do-mesticating these terrible hollows. For a moment that now seems irretrievable, the debris of war had become the peacemakers' triumph. With glee and much fanfare, they fashioned the cozy honey¬comb of family life—kitchen, den and dining room, bath, bed and study—within the concrete and steel interspaces of missile pods. Housebroken silos may well be relics of the cold war, but unlike the Berlin Wall, nuclear weapons and the strategic threat to use them re-main with us.

After the events of September 11, 2001, after the Bush administration's relentless push to generalize vigilante action beyond the frontiers of Afghanistan into a global scourge, and especially in the prelude to the American invasion of Iraq, the menace of weapons of mass destruction unexpectedly lurched into public awareness. Yet even as Bush's deputies invoked the phantom threat of WMD as a goad to subdue skeptics into compliance with his foreign policy, the realities of war waged with these weapons is still hazy even now, a scary Something.

Tens of thousands of nuclear warheads are either already coupled to missiles or could instantly be made ready by the governments of the United States, Russia, China, Great Britain, France, Israel, Pakistan, India, and now, apparently, North Korea. Other states and, allegedly, countless insurgents and militants aspire to devise their own working bombs. Now, as in the cold war, we are menaced by the possibilities of nuclear war touched off by vengeance, pitilessness, dumb chance, or mechanical accident. This actual, this breath-stopping fact—the cataclysmic potential of nuclear war in our world describes our present. And yet even as you read these pages, it is instantly forgettable.

In 1960 Kahn fixed his attention on this elusive reality. Nuclear war was not improbable but possible, even likely, he said again and again, waylaying anyone who would listen to his unthinkable tidings. But then, and now, "it is almost impossible to get people interested in the tactics and strategy of thermonuclear war." The possibility of nuclear war was harder to think about than one's own death. It meant a death horrifically amplified in the opposing mirrors of the unimaginable millions cut down by such a war and the memory, fresh in 1960, of Hitler's gambling streak with British and French complaisance. Unlike the sacrifices of World War II or Korea, nuclear war offered no consoling wish for the future. Kahn once teased a friend, "I think we can get your daughter through grammar school alive."

The man, attuned to his brassy wit, told me he was comforted by the remark. In 1960, most people couldn't bear to hear about nuclear war in the present or future. (4)

Rather than addressing the possibility of war in the tense quaver of mortally frightened peaceniks, Kahn was buoyant and ingratiating. He was appealingly eccentric: grossly fat, a stammerer and wheezer, nearly narcoleptic at times, but, when awake, insatiably chatty. No one knew what to make of him. Was he a bad man but likable? A good man but flawed? A fiend or a gadfly? One reader thought Kahn's book, On Thermonuclear War, was "a moral tract on mass murder: how to plan it, how to commit it, how to get away with it, how to justify it." Another thanked him, gulping, "All nonsense about conventional praise aside, the country—probably the world—owes you a great debt." Decades later in his obituary, critics clucked that On Thermonuclear War "should properly have caused the sequestration of its author into psychiatric care."

Yet the reviewer for a New York chapter of a humanist association praised him for moral excellence. "He determines truth through empirical observation and logical reasoning...What else is more akin to the spirit of humanism? Kahn has the courage to face whatever facts are uncovered by his rational search for truth, and to publish the findings despite national furor." (5)

Certainly according to his own lights, Kahn was heroic. He dedicated himself to the most unpalatable crusade imaginable: persuading his neighbors that nuclear war was an immediate peril, and rousing them to prepare to be struck, fight back, and survive. He was fearless and persistent. He was also quixotic, banging together a snuggery of civil defense from a tissue of death-denying wishes. He spoke of Life implacably braving the immensities of weapons effects. He miniaturized the cosmos into human scale by focusing on the practical necessities of survival and recuperation—whether the stock laid aside for the atomic homestead would be enough, whether food and other provisions would hold out. Life, in his view, was not frail, but adaptive and nimble.

Casting nuclear war-fighting and the postwar world into specifics, Kahn worried about genetic mutations in the survivors' children, about soil decontamination and the resumption of agriculture, about an automated deterrence system that could bind the planet into a network of irreversibly computer-triggered bombs. Yet, while he warned America to prepare for nuclear war and repeatedly urged its citizens to accept the legitimacy of striking first should the Red Army threaten NATO countries, he also obsessively enumerated the very uncertainties that dissolved his affirmations of survival into the bracing Nothings of hope.

Attaining the summit of prophecy—"any picture of total world annihilation appears to be wrong, irrespective of the military course of events"—he bumptiously reversed himself and pointed out the blind spots in his scenarios of war and reconstruction. Scrupulous and disarming, he repeatedly laid bare the various suppositions that composed his belief in Death-defying Life. (6)

It is painful to imagine in unforgiving detail the unthinkable worst that humanity can do to itself and to the world.

For us, this means war waged with biological, chemical, nuclear, and radiological weapons, but also cyber-attacks, climate change, pandemics, species extinction, desertification, drought, population explosion, genocide, resource scarcity, and pollution. These abstractions connote many shapes of shared earthly death, real possibilities but too painful for most of us to examine intently. I do think it was brave for Kahn to ponder the limits of his present moment. But it was folly to down-play the scientific uncertainties that engulfed his prediction of post-war survival. And more than folly to sweep aside the morality of fighting a war with weapons that would vaporize millions of innocent people in a single campaign.

Kahn neatly sidestepped the moral and social costs of fighting with genocidal weapons with a pragmatic murmur, "always abstracting from the humanitarian aspects." Not that he dodged the problem of nuclear casualties. Kahn was nothing if not brazen. He tackled the problem of the social legitimacy of state-sponsored violence head-on.

During the years in which he was formulating his arguments about nuclear deterrence, he would regularly demand that his briefing audiences answer the question, "If it is not acceptable to risk the lives of the three billion inhabitants of the earth in order to protect ourselves from surprise attack, then how many people would we be willing to risk?" It cut to the heart of his critique of President Eisenhower's strategy of threatening massive retaliation.

"It may be too much to promise to kill every Soviet citizen if they act up. I admit it might be

Chapter 1

HOW MANY KAHNS CAN THERE BE

Kahn does for nuclear arms what free-love advocates did for sex: he speaks candidlyofacts about which others whisper behind closed doors.

Aimitai Etziqni,196l

Is it too soon to pivot round to peer at the half-century just behind us and contemplate its dreamers, its optimists and crotchets? Too soon to make out the soap bubble of the cold war that arced over our heads and seemed as durable as the landmarks that orient our world? This is a book about a buoyant man, a storyteller and visionary of the thermonuclear era.

He masked his stories in the bloodless dialect of probabilistic risk assessment, but they were stories nonetheless. This is about world-making, and about someone who happily huddled with other men at RAND to cast an alternative present and a suite of alternative futures. Herman Kahn was especially good at imagining survival against unbearable odds, and at telling stories that detailed the life or death of the nation.

The hero of these tales was not a warrior but the ultra-modern lion of advanced industrial culture, the civilian defense intellectual. The eggheads at RAND, and this art¬less, sweaty man in particular, did not set out to conquer a world but to save the future with stories cocooned in numbers, stories of cunning and foresight and daring, of fortuitous invention, and the resurrection of spring.

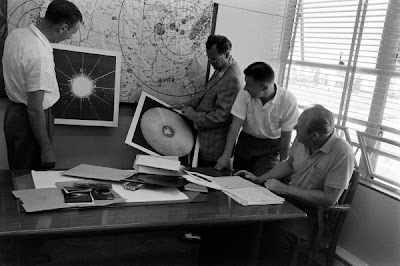

During the 1950s Kahn worked as a systems analyst at the RAND Corporation, the air force's nonprofit research institute. We can hear him briefing visiting air force officers: "I gather you can't see this from the back of the room. You can see them? Fine! You've got 20-20 vision though. (He's my boss, and I can't tell him what I think of him. Well, I've got plans under way though, and boy, when I... )" (1)

He has a Bronx accent. There's pressure against the sinuses, some wheezing. He stumbles over some words. He gulps in a breath and grins. "You see, ideally, what we would like to do is get the models of your bombers, send them over to Russia, see how many get shot down, how many get through, let them run over their bombing runs, then come back. But you can't get cooperation in doing this. It's the kind of thing which seems to be impracticable currently.

I've talked to some people, though, who practically want to try it this way, but even these guys sort of talk very quietly. With more a sort of a feeling of longing, than really believing in doing it." (2)

This chubby young man in eyeglasses, clutching a pointer, tottering at a lectern flanked by easels with charts, perspiring freely, blurts out, "I might mention that—just interrupt me anytime you want with questions, this being really set up as a demonstration-audience participation lecture. We don't want argument, but we're willing to take questions." The audience laughs.

"This is serious. I speak as a man who's been wounded. I've got stories to tell which would curl your hair!"(3)

Speaking of World War III, he wags his head. "The Russians aren't dedicated world dominationists. You know, they just sort of want it on account of a sentimental way, you know, but not like 'By God, we got to have it!' It just doesn't make sense for them to really push too hard, you know, but just to push easy." He flips to a drawing of a spindly boy wearing oversized glasses, hugging an ABC primer, and sniffing a daisy. This is the enemy.

"The first [mistake] is to assume that he is a sort of cretinoid idiot, who can't see, think, or anything. It might be a fair, if dangerous, assumption that the enemy is at least as stupid as we are." The next picture is a Goliath with four arms, reading a book, lofting a 1000-pound dumbbell, aiming a pistol at a target, painting a picture. The enemy can do everything. "He's a giant, seven feet tall with four arms, each with two biceps. Each arm can, of course, be used independently and simultaneously." (4)

We can tell from the crewcuts and bowties that we've crept up to Kahn sometime in the 1950s.

Some men in the audience wear uniforms; others are in suits. Most are in their twenties or thirties. There are a number of women in the back who look like secretaries, but others sit among the ranks of analysts and officers. Here is the lithe daughter of Admiral Nimitz who combs Pravda for tidbits. Over there is a woman who spends her days sifting through Japanese signal intercepts collected before the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor.

He ambles along the platform.

"Lots of times people say about systems analysis, why don't you guys do an experiment? What the hell are you sitting here figuring things? Why don't you go out and run an experiment? Well, we'd love to run experiments, but there are two difficulties. One, in realistic experiments, people get shot down. That's not the major difficulty. We're willing to do it." The audience laughs. "We are. The real difficulty is we're talking about weapons which aren't in existence yet." (5)

A young man bounds on stage with an armload of charts. Kahn cocks his head and mutters, "Why don't you just split this up a little bit. Put them over there. No, don't just hold it. Well, you just stand. When we first gave this thing, it was sort of a rush job, and he'd been up about 24 hours in a row for quite a while, so he just really couldn't stand." He cackles. "That's no longer the situation. He can stand now. I mean, things have changed. I don't need you anymore." (6)

Kahn whips through the next bit. "If you assume that your job is to defend the 20 largest cities against surprise attacks, this is hopeless unless you assume the enemy is stupid. It doesn't matter what you do, it will not work unless the enemy is stupid.

So if you assume this is your mission, you might as well assume the enemy is stupid. But it is not stupid to assume the enemy is stupid, because this is the only [way] this thing could work. Assuming he is stupid, you can save a great deal of money. You design your system against this stupid enemy. [But] he just ain't that stupid. He writes in classified papers that he ain't that stupid. He explains it to you, understand. So it's very hard to believe that he is. It's a little stupid to believe that he's that stupid." (7)

He nudges his assistant. "Want to give me this next one? Oh. He argues with me. I mean, if a guy is right, he ought to be very polite." The young man flits away. Kahn snorts happily. He's found a great way to talk about pitfalls in modeling hypothetical problems. One of the office secretaries drew a cartoon of a man mamboing with a female dummy. He flips to this drawing and gazes at it. "He is either desperate or guilty of Modelism.

We could just as well have shown a young man looking at pin-up pictures, or any situation where somebody is playing with an ideal in preference to the real thing. It may or may not be desirable for a young man to construct his love life around fantasies, but the mature heterosexual male wants a girl!" (8)

He slurps a mouthful of water and races ahead. "One of our col¬leagues points out that the analogy is unfair to the Systems Analyst. There are delectable girls all around to tempt our 'mature heterosexual adult' away from his dummy, but what can our poor Systems Analyst replace his model with? Another one! Even if he wanted a war, he couldn't have it. Of course, as any psychologist will tell you, the comparison is not so unfair. Some fantasies are nicer than some real girls!" (9)

The next cartoon shows a man steering a roadster off a crook in a mountain road, distracted by a buxom woman gazing at the view. He jabs a finger at the drawing and tries to suppress a giggle. "Another mistake which is very very important is over-concentration.

This is the kind of thing that, for example, you see: he's just concentrating not on the wrong thing—its worth looking at, but not exclusively. We don't object to you looking at the blonde. We'd look at her ourselves [but] you should look at something else. There's a cliff over here. And the point is look around, look for loopholes, see what's happening." (10)

And there was that novel about pushbutton war. Everyone is talking about launching missiles by mistake. "You're worried about somebody making the wrong connection. You know, he puts the fuse in when he should have taken it out. He turns the dial just for kicks.

He presses the button because he likes to look at the red lights. You know, you people work with computers, you know that people just literally can't resist passing without pressing buttons. I'm one of them myself, I've got to hold myself." (11)

Thinking of the next thing he's going to say, he beams. "You re¬member there was this legislation passed by Congress saying you can't study surrender. My wife looked at it and said, 'Herman, I got a funny reaction to this.' I said, 'What do you mean?' She said, 'Well, if it ever occurs that I'm cowering in a cellar, and they've hit us, and they've taken out a certain amount of SAC, a lot of air defense, and bombs are dropping near me, I'm sitting there with my two children, I'm going to consider the question.'" He shrugs. "I can be funny on the subject of thermonuclear war," he once said to a reporter. (12)

When Kahn's house in New York was being built in 1961, an appreciative producer of seamless concrete cylinders—aware of his zeal for civil defense—offered to donate materials for a family fallout shelter.

A hole was excavated near the outer wall of the living room. Before the shelter was installed, Kahn was asked to test its design by wiggling through the pipe that served as its entrance. It was impossible—he was too stout. Infuriated, he ordered his workmen to widen the cavity to accommodate a swimming pool. It was embedded inside the house in a long chamber adjoining the living room. Addicted to swimming, Kahn would slip into the waters of his pool in the mornings before breakfast or late at night.

I picture myself on an early morning in 1962, gazing at draped windows and one glowing spot. A splinter of light darts onto the driveway. The house looks no different from the other ranch houses on the street. Not opulent but comfortable, tucked in a shady cul-de-sac.

All is homey and familiar, yet that lamplight discloses a swim¬ming pool encased within the husk of a residential fallout shelter. I imagine Kahn shuttling back and forth, counting laps, daydreaming about the day ahead, the books he's read recently, his current fads and preoccupations. I imagine the fertile seclusion enveloping the swim¬mer: the flush of sound, water bubbling in the ears, the ringing gurgle and deafness of immersion. The swimming pool is a medium for the fantastic: an earthbound man glides to and fro weightlessly. Swimming in a short pool amplifies the effects of relaxed and flopping effort. Swimming transports man out of niggling little life into the purest sensations of resolve, unseen and bobbing in water barely heard, beyond the black facade of daybreak in the suburbs in 1962.

Here is Kahn frisking in the surf on Santa Monica beach. He tumbles into the water happily. The ocean suits him, its soft tug, his sprawl through swells and foam. Here is Kahn counting laps in his new house in New York. So many people want to find him and talk to him. A housewife peers out of her window, forlornly blessing the blue sky. She wonders if she is crazy to brood so much about the end of the world. "For the last month or so I have seriously been in doubt as to my sanity," she confides to Kahn. "I weep at the thought of a surcease of human existence, perhaps of this beautiful earth that I love so well itself." She feels alone in her fears, she tells him in her letter. Her friends mock her. "Most people want to know if I am some 'new kind of nut.'" Those with more finesse say, "If it happens, it happens." What to do, Mr. Kahn? "I am afraid," she whispers. "I wish to survive." (13)

A junior high school teacher snatches a tray of cookies out of the oven. Inhaling sugar, butter, and chocolate, she frowns, "Is this enough? Can I bear it?" Having pottered and loafed for days, she finally sits down to write. "Dear Mr. Kahn," she says, "I have spent a painful weekend, thinking, watching TV reports, thinking and intermittently seeking relief in cookies, bike rides, not thinking and trite household chores. I am in the audience of the near-panicked . . . My intention in writing you is not for you as my 'Fairy Godfather' to whisk away the problems that cause my fright [and] flight." She wants help for enduring. "How can I better prepare myself [and my students] for the task of maintaining mature mental and emotional attitudes . . . and faith in ourselves as cooperative individuals under stress (attack or not)?" (14)

The wife of a doctor and mother of three children suddenly realizes war could strike at any moment. "I am not afraid to think!" she wails. "I am a Christian, but I am not hiding behind God, letting Him take care of things." Even so, realistic preparation for nuclear war was unspeakably hard to grasp. She works it through: "Suppose we built a bomb shelter in our yard. Would the days that we could survive there actually help? What would happen when we ran out of food and water?...What if I do read articles telling me what to do in case of attack? What good will it do me if everyone else in Los Angeles is dead? My husband's hospital is 20 miles away. How could I, alone, care for three children under three years old?" Yes, nuclear war was a real possibility, but Mr. Kahn, "What are you trying to ask us to do? I feel the urgent need to do something now, but what can I do?...Please tell me what to do now! What should I read? To whom should I write? If you will give sound advice, I will heed it!" (15) But maybe preparation for survival will not safeguard the future. Maybe survival was a cosmic daydream. A young man spends his days teaching his kindergarten class, wondering whether his wriggly moppets will grow to adulthood. "No, Mr. Kahn," he admonishes, "it is hard not to feel that in your desire to persuade people to think seriously about nuclear war by persuading them that it may not be as bad as they think, you have skipped over a good many problems." But later that year the young teacher is struck by a joke. A reporter from

What you seem to me to be thinking, perhaps just hoping, is that...life after World War III might be much better than life today. It is as if you thought of yourself as one of a number of Noahs, stepping out into a new world for a fresh start. I don't blame you... who would not like to see cleared away... the ugliness, horror, and corruption of today's world; who would not like the chance to deal with real problems that might be solved, instead of problems that only lead to more problems, and thence to still more?

But if his life was really abnormal and unhappy, maybe he should redirect his attentions. "If you get tired of making calculations about 100,000,000 dead versus 80,000,000 dead ... you might try teaching young children. They might convince you that they deserve a chance to make more of their lives than their elders have of theirs." (16)

A band of men and women bearing placards and canteens trudge across the Southern California desert on their way to RAND to talk about the Bomb. It is 1960, and they hope to walk across North America, across Western Europe, and talk to Muscovites too. But first, they arrange to chat with Kahn in a cabana at the Del Mar Ho¬tel and Beach Club. He is the only one from RAND who greets them. "I was surprised at his friendliness and his democracy," one of the marchers remarked.

"He wanted to talk with us and he was willing to go out of his way to do so." They talk about World War III. Kahn says he thinks "thermonuclear war likely within ten years if arms control or disarmament agreements couldn't be reached." More than forty years later, Bradford Lyttle, a lifelong peace activist, would single out Kahn for special praise. "I maintain this rather warm feeling in my heart towards Herman Kahn. Even though I felt that many of his ideas were appalling and seemed to be very cold-blooded, personally I found him much more approachable and really more under-standing of our position than a number of people in government I talked to." (17)

"Is There Really a Herman Kahn? It Is Hard to Believe"

In the 1960s Herman Kahn was a well-known man. His name alone broadly signified contemporary affairs. Jules Feiffer twitted him in a lampoon of East Coast foreign policy elites. Susan Sontag invoked him in an essay on science fiction films. The composer Luigi Nono even borrowed text from his book On Escalation in a work dedicated to the National Liberation Front of Vietnam. Kahn himself quipped, "I am one of the ten most famous obscure Americans." (18)

His first book, On Thermonuclear War, published in December 1960, was the first widely circulated study that dramatized how a nu¬clear war might begin, be fought, and be survived. A reviewer in The Village Voice remarked that the book "shocked us into paying serious attention, for the first time, to what our military thinkers, planners, and doubters were thinking, planning, and doubting. Never has so much been publicly written and read about war; never has there been so much open and respected exploration...of a nation's military policies. (19)

OTW, as it was popularly known, made Kahn a celebrity. He appeared on TV and radio, in magazines and newspapers, exhorting the nation to muster the will and wherewithal to fight and survive a nuclear war. The book and its author were the subject of editorials, letters-to-the-editor, and college debates. Nearly everything said about him contributed to the feeling that Kahn was a man of the times, but no one could agree on what he represented. Was he a hero-scientist or an American Eichmann? A human computer or a humanist, a patriot or a psychopath? Stacks of letters tipped onto his floor from military and civilian officials, journalists, students, peace activists, veterans, civic organizations, even manufacturers of fallout shelters and survival equipment.

In 1961 it seemed as if everyone wanted to solicit Kahn, argue or plead with him, schedule lectures and meetings, arrange publications and sponsorships. He was invited to address the War College at the Air University, the senior class of the Air Force Academy, and officers attending the National War College. He briefed President Kennedy's assistant secretary of defense for civil defense and met with the Senior Seminar in Foreign Policy at the State Department's Foreign Service Institute. He testified before congressional hearings on civil defense.

He addressed members of the U.S. Civil Defense Council in Los Angeles and the Dallas Symposium on Civil Defense. He spent a day hobnobbing with the Lexington Democratic club in Manhattan. He attended the Behavioral Science and Civil Defense conference sponsored by the National Academy of Sciences. At the annual meeting of the American Political Science Association, he joined a panel on "promoting research on war and peace."

Kahn was invited to become an adjunct professor for the UCLA Institute of International and Foreign Studies. He accepted a position on the advisory council to a newly hatched Peace Research Institute in New York. He addressed the Commonwealth Club of California, celebrants at the MIT Centennial festivities, and the students of Oak Ridge High School. The Women's National Press Club and the North Texas Section of the American Nuclear Society engaged him to speak. He debated the wisdom of civil defense with a Harvard philosophy professor and spent a day exploring the possibilities for peace with the American Friends Service Committee at their annual Roundup. (20)

The publisher Frederick Praeger invited him to write a book on foreign affairs. The editor of Encounter wanted his thoughts on the furor over OTW. The chief of the editorial division of the Organization of American States and the editor of a union periodical asked him for something on civil defense. He corresponded with the peace education secretary of the American Friends Service Committee; the editor of the radical Committee of Correspondence newsletter; the director of the Environmental Radiation Laboratory at New York University;

a scientist adapting manufacturing processes to the lunar environment; an arms controller reporting on research on radiation absorption in human tissue; and an inventor of a weather control system that would induce rainfall by spreading carbon on the surface of drought-stricken regions. All of this took place during the year that he left RAND and founded his own research organization on the East Coast, the Hudson Institute. (21)

While some readers welcomed his frank exposition of possible war, others pounced on his ethics and mental health. "Mr. Kahn is now cast for the role of Chief Fascist Hyena," scowled a political scientist. He was pelted with a flurry of personal attacks, the first and most famous of which was James Newman's sarcastic review in Scientific American: "Is there really a Herman Kahn? It is hard to believe. Doubts cross one's mind almost from the first page of this deplorable book: no one could write like this; no one could think like this." The science correspondent in The Glasgow Herald denounced Kahn's book as the work of the devil:

"Not the traditional devil, reeking of brimstone and tempting men to old-fashioned sins, but a slick, talcum-scented, contemporary Satan, rationalising hideous emotions by reference to strategic studies, electronic computers, contingency planning, and all the other gimmicks of paranoiac gamesmanship." In his defense, a Berkeley psychoanalyst championed the maturity and courage required to "face the worst fearlessly." In a letter to The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, Dr. Walter Marseille interpreted antagonism to Kahn as "a widespread and deep-seated emotional resistance against the possibility of nuclear war as part of the reality with which we are living." (22)

OfHcial Washington regarded OTW as exemplary work from RAND. While he would never become a Kennedy insider, Kahn's ideas were well known because many of his RAND colleagues had fled into the new administration. Alain Enthoven, the nation's first (deputy assistant) secretary of defense for systems analysis, welcomed OTW, writing, "I am most impressed by the scope and the extremely high density of ideas." Reprising his own reasons for quitting, Enthoven regretted that so many "important ideas on strategic problems" had been buried at RAND, "where they are sure to have no beneficial effect on policy.

Your book," he concluded flatteringly, "represents an enormous break in the log jam." A year or so later, the secretary of defense's special assistant, Adam Yarmolinsky, greeted an audience at Kahn's new think tank with the comment, "For the past year and a half, we at the Department of Defense have been living off the intellectual capital accumulated by Herman Kahn and others in this audience." (23)

OTW was hotly debated in military circles, especially in the air force. It was the main selection for the air force-sponsored Aerospace Book Club for January 1961 and was offered as a free premium for new members. Among the earliest public notices, the Bulletin of the North American Air Defense Command recommended OTW as a "reading must." A handful of letters reported that his book had been passed around at military bases, the subject of eager discussion. (24)

Readers were thrilled and alarmed. Some thought OTW was hair-raisingly engrossing. "It is the most exciting book I've read in years," exulted a political scientist...

Acknowledgments

Martin Collins, David Hounshell, David Jardini, and Andrew May were the first historians to peruse RAND's archival holdings in the 1990s. I have relied on their research for important source material. The National Defense University at Fort MacNair in Washington, D.C., has a Hudson Institute archive. There are more than a dozen boxes of Kahn's papers and correspondence in this collection, dating from 1961 to his death in 1983.

The rest of Kahn's papers remain in his family's possession in Chappaqua, New York. In 1991, Kahn's widow graciously allowed me to examine a half dozen boxes of her husband's papers from the late 1950s. I am grateful to the late Jane Kahn for hosting my visit so long ago, and to Drs. Collins, Hounshell, Jardini, and May for sharing their research with me.

This book has been sponsored by so many institutions, has been helped along by so many friends, it gives me great pleasure to ac-knowledge them. I am indebted to the following:

• A Humanities Division Graduate Research Grant, University of California at Santa Cruz for travel, as well as the extraordinary expenses of transferring kinescope negatives of two television programs featuring Kahn in 1961 to video¬tape.

• A Smithsonian Graduate Student Fellowship, Space History Division, National Air and Space Museum, summer 1991, sponsored by Martin Collins and Space History Division Director Gregg Herken. Collins's expertise in RAND matters guided my early years of research. His generosity and friendship remain dear to me.

• An Institute for Global Cooperation and Conflict Dissertation Year Fellowship and UC Regents Dissertation Year Fellowship, 1992-1993. I happily acknowledge Barbara Epstein, who encouraged me to pursue the topic; Andrew Feenberg, who offered theoretically fruitful suggestions; and especially Donna Haraway for encouraging my attempt to conjoin the history of science with critical theory, and for befriending me at a critical time.

• A Postdoctoral Fellowship in the History of Science, History Department, Northwestern University, 1993-1994. Thanks to David Joravsky for sponsoring my fellowship, and Ken Alder and Bronwen Rae for their affectionate hospitality.

• A Postdoctoral Fellowship in American Studies, The Commonwealth Center for the Study of American Culture, The College of William and Mary, 1994-1996. Thanks to Chandos Brown for sponsoring my fellowship; to fellows Grey Gundaker and Patrick Hagopian for their staunch friendship; and to Arthur Molella of the National Museum of American History for his friendly interest.

• A Postdoctoral Fellowship in the History of Cold War Science and Technology, Carnegie Mellon University, 1996-1998. Thanks to David Hounshell for sustaining me with two years of fellowship, for generously entertaining my ideas which were as far in taste and temperament from his as could be imagined, as well as for his insights into RAND's organizational culture and the social role of the cold war entrepreneurial scientist-administrator. Thanks to the members of the cold war research group, Glen Asner, Jennifer Bannister, Doug Davis, Gerard Fitzgerald, Joshua Silverman, and Ruud Van Dijk, who astounded me with their generosity, energy, and collegiality; and to CMU's librarians, Joan Stein and Geraldine Kruglak, for their persistence.

• A Senior Research Fellowship at the Center for the Humanities at Wesleyan University during 1998-99. Thanks

to Elizabeth Traube for sponsoring me, and to the other Center fellows, and to the Center staff, Jackie Rich and Pat

Camden, for a memorable year. Thanks also to the Wesleyan interlibrary loan librarians, Kathy Stefanowicz and Kate Wolfe, for their labors.

I am happily obliged to the friends and scholars who have offered corrections, suggestions, and editorial wisdom: the late Susan Abrams, Laurence Badash, the late David Edge, Lawrence Freed-man, Peter Galison, Grey Gundaker, Patrick Hagopian, Gregg Herken, Susan Lindee, Everett Mendelsohn, Charles Nathanson, Michael Sherry, and Fred Turner. I am especially grateful to my editors at Harvard University Press: Michael Fisher for gambling on me, Sara Davis for patient assistance with the art program, and Susan Wallace Boehmer for her sagacity, flexibility, exacting expertise, and appreciation for the finer points of the sick joke.

Heartfelt thanks are due to the men and women who allowed me to interview or correspond with them: Frank Armbruster, Lincoln Bloomfield, Sam Cohen, James Digby, Richard Frykland, Olaf Helmer, Jane Kahn, Carl Kaysen, Arnold Kramish, Bradford Lyttle, Irwin Mann, Francis McHugh, Everett Mendelsohn, Robert Panero, Gerard Piel, Steuart Pittmann, Walt Rostow, Henry Rowen, Gustave Shubert, Sidney Winter, Jr., Roberta Wohlstetter, and Herbert York.

I am obliged to Irwin Mann, Thomas Schelling, Max Singer, and Anthony Wiener for allowing me to interview them at length. Separate and special thanks are reserved for Daniel Ellsberg, Spurgeon Keeny, and Andrew Marshall, who read parts ofthe manuscript repeatedly and carefully, alert to errors, omissions, and over¬statements. Their critical suggestions and their willingness to explore this material with me thoughtfully helped make the book more accurate and more pointed.

Thanks to Victor Navasky and Richard Lingeman for sharing their collection of The Monocle and The Outsider's Newsletter; to J. Fred MacDonald for hosting a week-long scurry through his archive; to Peter Hornick for his hospitality in Manhattan; to Zhan Li and Doug Davis for research tips and help; to Barry Bruce-Briggs for the drive from the city; to David Kahn and Deborah Kahn Cunningham for their pleasant conversation in 1991; and to David Kahn for his later interest in the book.

David Kahn and Deborah Kahn Cunningham have given me per-mission to quote from their father's unpublished papers in their possession. However, they wish to make clear that they do not endorse the views, interpretations, and opinions that I have set forth in this book. Permission to quoted copyrighted material was also given to me by: Frances Burwell, Executive Director, Center for International and Security Studies at Maryland, for the Berlin Oral History Tran¬scripts; Hudson Institute, for Herman Kahn/Hudson Institute Ar¬chive materials in the National Defense University; MITRE Corporation Archives; the National Air and Space Museum; Princeton University Press Archives; and the RAND Corporation.

Tim Haggerty has earned my awestruck gratitude for gamely reading the long version of this book. And for their beautiful constancy, thanks flow out to Diane Bennett, Christine Collins, Sharon Josepho, Carol Kirk, and Barbara Powell. The love of my parents, Harvey and Randi, my brother, Charles, my other family, Maman, Bijan, Behdad, and Behjat, and the children of my heart, Megan, Donya, Jodi, and Mana, have fortified and inspired me.

Finally, this book is dedicated to my wise and gallant husband, Behrooz. Without the benefit of his witty, affectionate conversation over the years, the tempo of this book would have been more plod¬ding, and the pleasures afforded by it surely fainter. With great love and respect, I offer my thanks to you.

Contents

Prologue: A Matter of Faith 1

1: How Many Kahns Can There Be? 10

2: The Cold War Avant-Garde at RAND 46

3: The Real Dr. Strangelove 61

4: An Operational but Undetected Capability 83

5: How to Build a World with Artful Intuition 124

6: Faith and Insight in War-Gaming 149

7: The Mineshaft Gap 181

8: On Thermonuclear War 203

9: Comedy of the Unspeakable 236

10: Mass Murder or the Spirit of Humanism? 281

Epilogue: A Comic Philosophy 310

Abbreviations 319

Notes 321

Acknowledgments 371

Index 375

Copyright © 2005 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Ghamari-Tabrizi, Sharon, 1960-The worlds of Herman Kahn: the intuitive science of thermonuclear war / Sharon Ghamari-Tabrizi. p.cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-674-01714-5 1. Nuclear warfare—Philosophy. 2. Kahn, Herman, 1922- I. Title. U263.G49 2005 355.02'17'01—dc22 2004059697

Recommended soundtrack while reading this post!

0 comments:

Post a Comment